Brak produktów w koszyku.

Beliefs, music, language

Beliefs, music, language

***

Knowledge of beliefs and mythology greatly facilitates the understanding of Aboriginal culture, and thus becomes helpful in the reception of their art. For thousands of years, this art has been closely associated with religion, and many paintings currently painted for the Western market still depict sacred stories and refer to traditional beliefs and events. In this context, a painting serves a much broader function than formal and decorative modernist works. For the author, it is a testimony and proof of ownership of a specific area and conveys knowledge and secrets, the content of which is woven into mythology with the broad symbolism of everyday life. Knowledge, beliefs and art in this cultural system function inseparably and are manifestations of sacred creative acts and places where, according to Aborigines' beliefs, the energy left by the mythical Ancestors emanates.

What are these beliefs and what do they concern? Contrary to popular belief, Aborigines never created one religious system, just as they did not have one common language. There are hundreds of myths and stories and thousands of sacred places known throughout the continent.

Unlike followers of other religions, Aborigines did not make sacrifices or pray to allegorical representations of gods, nor did they build temples; the entire surroundings were a great open-air cathedral. The basis of these beliefs are events referring to the Times of Creation, when mythical Ancestors created all geological formations and passed on to people laws and rules of conduct.

According to the Aboriginal worldview, the world did not come from nothing, as in the Christian tradition from the Word, or as a result of the Big Bang, as cosmogonic theory claims, but existed originally, unformed. In the beginning, the Earth was a flat, empty surface in darkness, silence and chaos, with potential life forms lying dormant beneath its surface. The Mythical Ancestors broke the earth's crust with a loud bang and came to the surface. The sun appeared in the sky and the Earth received light for the first time. Ancestors wandered, hunted, fought among themselves, set up camps and shaped the landscape along the way. Finally, they created plants, animals and humans. At this time, in the Age of Creation, the present world was created and all truths about it were established once and for all.

The English terms Dreaming or Dreamtime have recently been used to describe religious myths related to the Time of Creation, which should not be confused with dreaming or dreams. Paintings painted for commercial purposes are also often titled and described in English, for example Fire Dreaming, Snake Dreaming or simply Fire Story, Snake Story, etc. Individual aboriginal tribes, which to some extent means linguistic groups, had separate names referring to to world events.

Thus, in Central Australia the term Tjukurrpa (Warlpiri, Pintupi tribes), Alchera (Arrernte) is used, and in the north among the Yolngu people - Wangarr. The scope of the concept of Dreaming is wide and may refer both to the Age of Creation and to a specific history or mythical event, which have separate nomenclature in Aboriginal languages. To own the myth of Creation is to be "a curator” of a specific area where the person-owner does not have to ask anyone for permission to hunt or use wood to make tools.

Fig. 1. Anatjari Tjampitjinpa (1927-1999, Pintupi tribe), Tingan", 1996, acrylic on canvas, 91 x 91 cm, Robert

C Collection. Tailor, Sydney

In Central Australia, human beings usually appeared partially formed, intermediate forms between the plant and animal worlds. The transformation into human forms occurred as a result of the act of transmitting spiritual values to people by the Ancestors: Honey Ant, Kangaroo, Sweet Potato Jams, Rain, Fire, etc. Thus, Ancestors and totems in Aboriginal religion may be animals, plants or geological formations, or phenomena or objects such as fire, rain or honey. Not only myths, but also the personal characteristics of the Ancestors are part of the identity of those Aboriginal people who own them. If the Opossum Ancestor was curious, the Lizard was unpredictable, and the Eagle was dangerous, these characters will be inherited by humans. Often several people or a group may share one myth, which functions as a kind of identification mark and proof of ownership of a specific area.

Mythical Ancestors, according to the beliefs of the tribes from Central Australia, came from under the earth or came from the sky, while according to the mythology of the peoples living in coastal areas, the Ancestors came from across the sea. One of many stories from the semi-arid lands of the center of the continent both presents the myth of Creation and explains totemism. The Arrernte people believe that at a time when there was no man or woman on earth, the western sky was inhabited by two Beings who came from nothing. Once they came down to earth and formed many incomplete human figures, without limbs or senses. These unformed beings would eventually become men and women, but at this transitional stage they looked more like plants and animals than humans. When complete transformation occurred, each person maintained a close connection with the animal, plant, or object with which he or she had been identified during the creation process. Therefore, each person has a special relationship with his totem, which connects him with the Time of Creation, and if it is an animal, such as an emu or a kangaroo, the meat of these animals should not be eaten by the owner of the totem.

Mythical Ancestors had supernatural features, they were partly similar to animals, plants or people and could take any shape, and their transformations took place in various directions. After completing the work, some of them disappeared underground, others transformed into characteristic features of the landscape, becoming sacred mountains, rocks, cliffs, water wells; some of them returned to heaven. In the Aboriginal spiritual tradition, the journeys of the Ancestors have both a symbolic and physical dimension. Sacred energy is concentrated in the places where they stop and camp, and the formations resulting from their actions constitute important elements of the landscape. Modern Aborigines are the heirs of spiritual Ancestors whose journeys and deeds are constantly recreated in ceremonies and rituals. This establishes unbroken continuity and connects contemporary existence with the Age of Creation.

The migration routes of the mythical Ancestors cover a huge area, which is why the stories related to them are often continued in the mythologies of neighboring tribes. Such an extremely rich collection of stories is the Tingari cycle, which forms the main group of Creation myths for the Pintupi tribe from Central Australia. These are stories about the journeys of Ancestors who stopped in particular places and then wandered further, sometimes even underground. Each of their stops left traces in the field and creates an independent narrative thread, at the same time being a link in a larger epic, continued in other places.

The ancestors of the Tingari formed groups of mythical men who were responsible for acts of creation and gave rights to people. Like humans, they were not perfect and had human weaknesses: they committed betrayal and sexual excesses, they were greedy, but they were also guided by noble motives. The ceremonies associated with the Tingari cycle are secret and should not be seen by women or children, as they are presented during initiations of a higher level. Adepts sing songs, perform rituals and, like the Ancestors, travel to secret places.

The Tingari theme appears often in contemporary acrylic painting. Paintings on canvas refer to traditional patterns painted on the body and to mosaics on sand made during ceremonies. Artists present this cycle in the form of concentric circles and lines connecting them, or only in the form of squares (Fig. 1 and 2).

The circles in this context represent the stopping places of the Tingari Ancestors, and the grids of lines represent the routes of their migrations during the Time of Creation. These images are also encrypted maps of areas where the exact locations of places are known only to the authors. In the initial period of the development of acrylic painting (Papunya settlement 1971-1974), paintings for sale depicting Tingari were painted away from women and children, because they contained many secret patterns of a sacred nature. However, over time, dangerous elements were withdrawn or replaced by others, and artists no longer reveal full information about their meaning.

Fig. 2. Barney Ca mpbell Tjakamarra (Pintu pi strain), Tingari, 1999, acrylic on canvas, 90 x 61 cm, collection of Galeria R, Poznan

Fig. 3. Warlukurlangu: What happened at the fire place, collective work of Yuendumu artists, acrylic on canvas, collection of the Museum of South Australia

A typical characteristic of individual Aboriginal myths is their close connection with a specific territory and the nature found there. The history of the Warlukurlangu fire, owned by the Jangala and Jampitjinpa kin groups of the Warlpiri tribe, presents a mythical event full of drama: “The old man Jangala and his two sons Jampitjinpa, while traveling, stopped at the place of Warlukurlangu. The sons left their father, who was blind, sheltered him from the wind, and went hunting. When the young men had gone away, the old man looked around, took his spears, and went hunting elsewhere. His sons didn't know anything about it, they thought he was blind. The father hunted some game, which he roasted in great haste over the fire, ate some of it, and buried the rest. When the hunters returned, they brought the meat and gave it to the old man, but he ate only a little. «Poor old man», they said.

Sytuacja ta powtarzała się przez wiele dni. Stary człowiek Jangala nieraz chodził spać z dala od obozu, mówiąc, że idzie w chłodniejsze miejsce. Ale tam przychodził jego święty mały kangur, który z nim rozmawiał. Pewnego razu młodzieńcy poszli na polowanie, ale nic nie upolowali. Wracając do obozu, Jampitjinpa zobaczyli małego kangura, którego zabili i upiekli na ognisku. Stary człowiek jadł mięso z wielkim apetytem, a bracia nie powiedzieli mu, gdzie polowali. Po tym wydarzeniu Jangala przez wiele dni na próżno przywoływał świętego kangura, wreszcie się domyślił, że jego synowie go zabili, i wpadł w furię. Stary człowiek wywołał magiczny ogień, aby zabić myśliwych. Ci natomiast chcieli go ratować, nieświadomi przyczyny. Ale ogień byt zbyt duży i bracia Jampitjinpa uciekli na południe. Wszędzie, gdzie się zatrzymywali, ogień ich doganiał i palił ich członki…„. Dalsza cześć tego mitu należy do szczepu Pintjantjatjara, który zamieszkuje tereny położone na południe od Warlpiri.

This myth illustrates the drama and deceit of a father who punished his sons for breaking a taboo they were unaware of. Innocent young people die from magical fire, and the old man feels satisfied. However, the deeper meaning of this story refers to the practical aspects of protecting the environment and game, which is subject to taboo, and the punishment in this case was more important than family ties. The story also highlights the differences between ordinary animals and those that, like the baby kangaroo, had special features of a sacred nature. Fire symbolizes the practice of burning areas, fertilizing the soil on which, after rain, plants attracting animals grow. This myth is extremely important for the Warlpiri people, because the places where mythical events took place create a map of these areas; rituals have also been performed there for centuries. This topic is often discussed in painting. The two curved lines represent the aston against the wind; traces of migrations and stopping places in the shape of concentric circles are also shown, the multicolored background shows vegetation and fire (Fig. 3).

According to the beliefs of the tribes inhabiting northern Australia, the first people appeared fully formed or were born from the bodies of mythical women who were already pregnant. The main group of myths in the Arnhem Land region are beliefs related to the Wawilag sisters and the Djangkawu Ancestors. The story of the Wawilag sisters and the Witija snake is often depicted in bark painting, and its variations vary among tribes and clans. The Wawilag were the daughters of the Great Mother of Fertility Kunapipi (who rose from the sea) and form a series of ceremonies and rituals.

An extremely abridged version of this richly detailed story reads: 'Two Wawilag sisters were forced to leave their clan because they had engaged in sexual intercourse which was not permitted by law. Wandering through Arnhem's Land, the sisters hunted and named plants along the way. The older one had a child, and the younger one was very pregnant. At the Mirraminna well, the sisters decided to set up camp because they were tired and hungry. The younger one felt labor pains and soon gave birth to a child, and the older one lit a fire and decided to roast the hunted animals. But the opossum, lying on the hot coals, jumped up and ran away along the stream, and so did the lizard, the marsupial rat, and even the wild berries. This was because the owner of this land and animals was the mythical man Witij, who lived in a nearby reservoir.

The sisters decided to build a hut and the younger one went to collect the bark of nearby trees, but while doing so she spilled some blood into the stream because she had recently given birth to a child. The blood flowed in a stream into the body of water where the snake man, Witij, lived. The water pollution angered Witij, who transformed himself into a snake and caused heavy rain. The younger sister hid in the hut and watched over the children, while the older sister performed a ritual dance and sang to stop the rain. Suddenly, the Snake Witij began to approach the hut, but the younger sister joined in singing. This helped for a while, but when the sisters ran out of strength, the snake crawled through the opening into the hut and swallowed them and the children, then returned to its abode in the water. It soon turned out that the sisters were taboo food, and the snake returned them in great convulsions, and they turned into ghosts. However, the snake man retained the sisters' secret knowledge and ceremonies, which he now became the owner of„.

This story refers to the distant times of matriarchy, when women were probably the owners of secret items and rituals that were taken from them by force or stolen by men. The snake represents the phallus, and the opening in the hut represents the vagina, and the rain refers to the monsoon season. In the painting on bark, the Snake is depicted in the form of a spiral, with sisters and their children inside the oval form (Fig. 4).

The black dots represent rain and the footprints represent the sisters' dance. Sometimes ritual objects and landscape elements are also depicted. In traditional bark painting and sand drawings made for ceremonies, only individual episodes of this extremely detailed history were presented. Nowadays, however, the entire story is often painted for the needs of the market.

W mitologii z Ziemi Arnhema podkreślana jest często kreatywna rola kobiet w kształtowaniu obecnego świata oraz konflikt z męskimi osobnikami o wyłączność odprawiania ważnych obrzędów. Przykładem może tu być opowieść o dwóch siostrach Djangkawu i ich bracie, którzy opuścili swoją wyspę Bralgu i przybyli na kontynent. „Djangkawu zabrali ze sobą sakralne przedmioty, które nosili w stożkowatych koszykach. Podczas wędrówki nazywali zwierzęta, ptaki i miejsca oraz zakopali w ziemi sakralne przedmioty dla przyszłych pokoleń. Tam, gdzie wetknęli swoje wędrowne kije, wyrosły drzewa bądź pojawiła się woda. Wkrótce siostry zaczęły rodzić dzieci, które zaludniły te ziemie, dając początek klanom sekcji Dhuwa ze szczepu Yolngu. Po narodzeniu chłopcy byli kładzeni na trawie, aby wyrósł im zarost, dziewczynki natomiast przykrywano matami, aby chroniły ich skórę od słońca„.

The myth of Djangkawu concerns the Time of Creation, but also mentions later events, when women were deprived of their power and lost many important ceremonies to men.

Fig. 4. Dawidi Djulwarak (ca. 1921-1970, Liyagalawumirri clan),

Wowilog Sisters (Wowilog Sisters),

1967, natural pigments on eucalyptus bark,

109 x 54 em, Sotheby's Auction House, Melbourne,

46 No. 107, June 1996

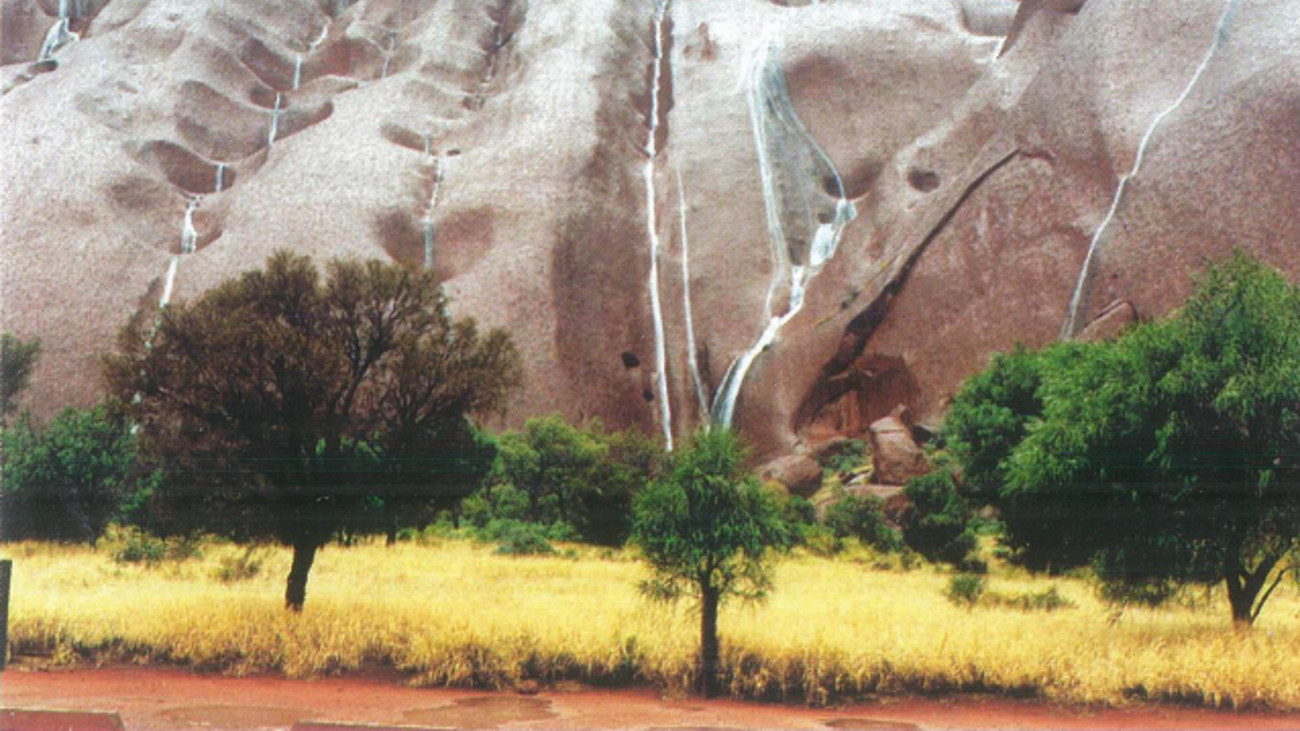

il. 5. Uluru (Ayers Rock), 1995

Mit ten ma dalszy ciąg: „Kiedy ich synowie dorośli, ukradli matkom sakralne parafernalia, rytualne pieśni i ceremonie. Siostry odkryły przestępstwo i podążyły śladami złoczyńców, ale nie były w stanie im nic zrobić, ponieważ ci śpiewali pieśni i odprawiali rytuały. Po długiej naradzie matki postanowiły wybaczyć synom, przekazując im więcej sekretów i pieśni. Po czym dwie siostry i ich brat powrócili na swoją wyspę„. Obrazy na korze przedstawiające powyższą historię Stworzenia podzielone są zazwyczaj na kilka pól, które symbolizują takie wydarzenia, jak podróż morska, akty stwórcze czy narodziny ludzi. Często też malowane są święte przedmioty oraz wzory klanowe przekazane przez Siostry nowym pokoleniom.

The most universal theme in Aboriginal religion is the myth of the Rainbow Serpent, which occurs throughout almost the entire continent. This snake is considered the great mother or great father of all forms of life. Its sacred significance is that it symbolizes both the phallus and the womb, thus being a symbol of fertility and fertility. In Central Australia, the Pitjantjatjara tribe believe that the Rainbow Serpent dropped his egg from the sky, which turned into a rock (Fig. 5) called Uluru (whites call this place Ayers Rock).

Jest to fragment książki Ryszarda Bednarowicza „Sztuka Aborygenów” (2004).